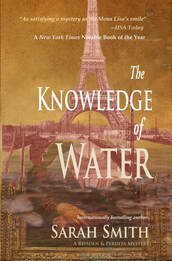

A bit of The Knowledge of Water

[This is from the beginning of the book, but a spoiler has been edited out. In this selection, the Baron Alexander von Reisden has been asked to identify a woman at the Paris Morgue--a woman whose murderer has written to him.]

The public viewing room of the Paris Morgue looked oddly like a theatre. The walls were grimy plaster furred with mineral deposits; the gaslit stage was marble, a white cheesy slab stained brown, separated from the audience by a glass pane running with moisture. Six corpses lay on it, dressed in the clothes in which they had been found, the bodies frozen and glistening. Seine water trickled under the slab, keeping them cold. Under the freezing chill and the smell of menthol and disinfectant, the air was unbreathable with the flowery whore's-talc of decay. The Mona Lisa was the colorful corpse, still drawing the eye: purple satin skirt spreading around her, red satin jacket, and several waterlogged postcards and parts of postcards, still recognizable as Leonardo's painting, pinned to her clothes. Over her heart her murderer's knife had ripped her jacket to pieces. Reisden remembered her on the steps by the Orsay train station, a wrecked beauty of a woman, standing with her eyes closed, singing in the ruin of a voice,kiss me, kill me, oh how I suffer,, shuffling and swaying and holding out her hand for centimes. She had looked like trouble, and now, to someone, she was. I wonder why he killed her, Reisden thought; I wonder how he came to it... Inspector Langelais pursed his lips. "I'll ask you to identify the letter." Limping, the Inspector led the way out of the viewing room to one of the tiny Morgue interrogation rooms. Through the walls Reisden heard the rumble of the Seine. The Inspector laid the photographic copy of the letter on the scarred table between them, then the original beside it, in a glassine envelope. The letter was written on the cheap greenish notepaper that is sold by the sheet in any post office. Cher mseur le Baron de Reisden, You like me you have lovd a Womn of Knidness Greace & Beauty She us Not Recthd the End of the Rivr war She was Mnt t Go It is not Rit that the Mona Lisa shd be in the Morg like any Comun Folk Ples Help Her Rtis "Why should he write to you?" the Inspector asked. "I have no idea." Painfully, with a sputtering unfamiliar pen, son Rtis had copied the engraved letters of Reisden's calling-card. "He had my card. He may have taken it when he killed her." "'You, like me, you have loved...,'" the Inspector pointed out. "He believes you knew her well enough to 'help' her. That means he knows you." Reisden shrugged defensively. "I don't know him." The Inspector pulled at his moustache-points. "What does he expect you to do?" "I don't know." The Inspector looked at his fingertips, rubbing the ends together. "She had been in the Seine for several days," Reisden said, "but her body was discovered yesterday morning and the story was in the afternoon papers. The letter came from," he picked the envelope up and looked at the cancellation, a slightly smeared RDULOUV over a red ten-centime stamp. "From the Hotel des Postes on the rue du Louvre. From the time-stamp, it was mailed at ten last night. Louvre is the only all-night post office. Yesterday afternoon or evening he read that her body had been found and taken to the Morgue; he had my card, which he took from her body; he immediately wrote me. The Morgue disturbs him." [There is no reason why 'Her Artist' should write to Reisden; but that is only one of the things that disturbs him. The other is the presence of Perdita Halley, with whom he has a very ambiguous relationship. She feels it as much as he:] In every sense except reality, Perdita felt she was Alexander's mistress. A respectable gentleman and young lady are never alone for more than ten minutes. She and Alexander had been together in a train compartment all night. They had stayed in the same resort town twice, for two weeks each time, though not at the same hotel. They had met each other on the beaches or at restaurants; they had talked about everything, the news, politics, his work, hers. She knew more about the chemistry of stimulus and response, which was his work at the Sorbonne, than if she'd gone to college, and he knew more about music. They had gone fishing in companionable silence. He had taught her to swim, at a pond in the country, alone. They wrote each other daily. A respectable young woman does not exchange daily letters with a man; she never signs them 'Love.' And if she does, she means it; she never accepts a man's offer of marriage, then tells him she won't marry him. They kissed, and more, too much for her peace of mind; sometimes only the touch of his hand would make her lose the thread of their good conversation. But they had not done the one final thing. What did she like about touring, that made her give him up for it? Touring was cold theaters and strange orchestras at eight in the morning, going through a conductor's interpretation for the first time that day when you were playing it that night. Touring was a month, or two, or three, living on sandwiches from railroad dining cars, sleeping in Pullmans if you were lucky but mostly across two seats; bringing your own tuning forks and felting files because half the pianos on tour wouldn't have been felted in this century. Touring was music: new orchestras, new interpretations, new colleagues and friends, constant challenge, constant performance. So she and Alexander had a friendship. An awkward friendship, that always made her worry it would slip down into being that and nothing more. [Perdita hires a house just outside Paris, where she can practice piano.] To have a house of one's own is an intoxicating thing at twenty-one. Twice a week, instead of practicing at the Conservatoire, Perdita would take the Madeleine tram-car to Courbevoie and spend the day. She would buy a bit of cheese, a demi-batard, an imported winter pear or an apple; she would practice all day in the lovely country silence, with the rain making a frou-frou against the windows and the fire whispering in the hearth; and as often as he could, Alexander was with her. He worked at the kitchen table; she would hear mail being opened, pages turned; sometimes there would be pencil-scratches as he took notes, and occasionally a 'Ha!' of triumph. He seemed, mostly, simply to be there, almost ignoring her, but sometimes, for a long time she would hear nothing, she would feel he was watching her through the doorway, and then her fingers would go clumsy and self-conscious; she or he would find an excuse for a walk, out into the rainy garden, to explore the fine old trees and the iris-pond and to escape the house, which had suddenly become too intimate. The most censorious watcher would have seen nothing to condemn. They were incautious, but respectable; it was a friendship. Only a friendship? There was a part of him she did not know, and it was what he would do if she let him do what he wanted. Outside the clear comfortable boundaries of their relationship was the unknown territory of Alexander. And a part of her was outside too, on the other side of a barrier whose existence they would be imprudent even to discuss. She thought about him constantly, his silences, his discretion, his presence. Late one stormy afternoon in early December, on a day when he was not at Courbevoie, Perdita went in search of dishtowels at the Grand Bazar, a fusty, musty, cluttered store for buying everything; and while she was there she bought sheets and bedlinens. There was a bed, after all; it might someday be convenient for her to stay the night; the Christmas and New Year's holidays were near, two long weekends one after the other, when the Conservatoire would be closed. But she took a long time, feeling everything, and bought the best quality, stiff thick sheets smelling of lavender and trimmed with embroidery, luxurious French bedlinens and a thick puffed French comforter, as if she were preparing her bed for a guest. ...And the rest of the story can be found in The Knowledge of Water. Enjoy! |

DVD Extras

New edition February 15, 2020.

430 pages. Trade paper, $15.99 ePub and MOBI $2.99 Preorder trade paper through Ingram-9781951636012 Universal book link for your favorite ePub site https://books2read.com/u/mVrPLp Kindle https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07ZDJSWYX |