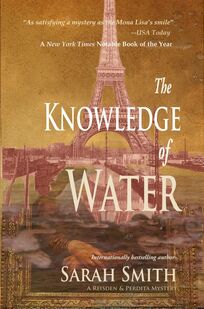

A Conversation with Sarah Smith

Q: WHY DID YOU choose The Knowledge of Water as the title for this book?

SS: Somewhere in Apollinaire’s criticism of the Impressionists he says, “One knows reality as one knows water.” In other words, reality is always changing; look away a moment, have a thought, and it’s different. That was the sense that modern artists like Picasso tried to give by painting a portrait from more than one emotional perspective—like the Demoiselles d’Avignon, in which the women are both idealized and demonic. I love multiple perspective; it’s something that novels can do better than anything else, because the drama of a novel comes from the clash of different points of view. What I’ve tried to do is paint a portrait of people in Paris at this turbulent time and make the book turbulent as well—flooding, pushing, and changing like water. Q: The Knowledge of Water is the second in a proposed series. Where did the idea in it come from? SS: I knew I wanted to write some books about the period before the First World War. The first book, The Vanished Child, took place in 1906. Nineteen fourteen I thought was easy: the First World War. But what came between them? Late one night I was wandering around my local bookstore in search of inspiration and came across the book Chronicles of Current Events in the Twentieth Century, published by Dorling Kindersley. I turned to 1910 and found a picture of the Paris flood. I had my setting! My copyeditor gave me Olga Samaroff’s An American Musician’s Story, which is where most of the Conservatory bits come from, and finally I mixed in some ideas about painting and forgery, because I was interested in how various cultures define art and how women artists fit into that time. Q: You’ve said, “Water is such a powerful thing.” What do you mean by that? SS: Have you ever been in a flood? We had one in Boston. It rained for days, and suddenly the water table was full and the ground became just like it was in Paris—impermeable to water. Between one hour and the next rivers flooded, basements flooded, and the power went out. There are times like that in people’s lives too. Emotion takes over, things change very fast, and afterwards, everything’s different. Q: Why was the 1910 flood so essential to this story? SS: The disaster and the emotional changes were important together; they fed on each other. For these people, love was the greatest disaster. For Alexander and Perdita it swept away certainties. It made Leonard paranoid. For people like Milly, love swept through and left the living room inches deep in mud. The flood was a perfect image. Q: How was Paris different before and after the flood? SS: The flood was Paris’s Titanic. Paris was the most modem city in the world. It had electric lighting everywhere and all-electric hotels. It had a subway system, the Métro, that was the best in the world, and a railroad system that was the hub of Europe. The French government knew the Seine was likely to flood and established a department to handle the problem. They had reinforced the quais; they had done everything right. And the Seine swept it all away. Q: How did you transport yourself to early twentieth-century Paris? Was it difficult to write about the flood? SS: If I had only known what I was getting into! I had to establish Paris twice—once before the flood and once during—and of course Paris was changing during the flood, so it wasn’t easy. I researched the flood through contemporary descriptions and civil engineering reports, decided on the historical events I’d use, and put them all together in a database (organized by Métro stop!). Then I went to Paris and spent three weeks looking at all the 1910 locations, almost all of which are still there. I went at the same time of year so I could pick up details like the look of the sky in winter. I also took a lot of photographs and collected postcards from the 1910 flood. A few of them are here. Q: You say Paris after 1900 was a wonderful place to be, but this was pre-World War I Europe—surely there must have been tensions in the air? SS: The French hated the Germans, of course, because the Germans had beaten them in 1870. But apart from that, things were fairly calm. Paris was a very cosmopolitan city, and the French firmly believed that any sensible person would want to live in Paris. A large percentage of the Parisian intelligentsia of the period were foreigners, as are most of the characters in The Knowledge of Water. There were tensions, of course. We’ll see more of them in the next book. Q: Strong, modern, feminist beliefs permeate this novel. Was there a “school of feminist thought” in 1910 Paris? SS: You bet! More of that in the next book too. Q: How did you research feminism? SS: There are two great research libraries specifically devoted to women’s history: the Schlesinger at Radcliffe and the Bibliothèque Marguerite Durand in Paris. I used both of them. Q: Do you believe women can have it all—love, family, and career? SS: We always ask that question as though it’s easy for men to have it all and only women have to struggle. I want to speak very carefully about this, because I don’t want to minimize the difficulties. Everyone has to struggle. Love that’s a genuine partnership between two people engaged with the world and each other; a supportive, loving home life; a career that makes a difference: they all take work. Men and women who “have it all” know how full their hands are. I think that many of us who want it all can get it, with patience and time and help— and a clear knowledge of what we don’t want and don’t need. Q: One critic has said the book’s main themes are “the supreme importance of art and the dilemma of creative women.” Do you think one is more important than the other? Do you think creative women today still have this dilemma? SS: I think that everyone who has two sustaining obsessions has this dilemma. Family vs. art, love vs. work, even partner vs. children. Women are historically cast as the caregivers and fulfillers of expectations, so they are often caught in that net. But I’ve seen many male writers get caught in the same one: they get married, they have children, and suddenly their wives are staying home for a year with the child and they have to find a job with health benefits. We all go crazy doing this juggling act, or we develop a sense of priorities (and a sense of guilt). Q: Some reviewers have said the book has too many story lines and characters. Do you think you lose impact or the reader’s attention because of these big plots? SS: I wanted to set up a book that would shift and change as readers picked one or another viewpoint on which to center. Books like that are traditionally hard to read— the classic example is Richardson’s Clarissa, which you have to read a couple of times before you even begin to get what’s happening. So perhaps I am being very clever. Or perhaps I did make it too complex; you judge. Q: You said in the book, “rivers are women, but a river in a flood is a man . . . angry and violent” (p. 324). Do you think this is true? SS: Oh, thank goodness for fiction. Leonard said this, and it’s true for him (and for Milly, and to an extent for Reisden, who’s afraid of his own violence). I can understand this point of view, and write it down, and learn from it, without endorsing or sharing it. And I don’t share it. Q: Several of your characters are loosely based on real historical figures, including Colette and Willy, Picasso, Gertrude Stein, and Guillaume Apollinaire. Why did you do that? SS: You can’t talk about Paris in 1910 without talking about art. Creating artists from the ground up seemed ridiculous, but I distrust the galvanized iron figures that stalk through most historical novels—“Leonardo da Vinci, meet Machiavelli”—so I gave them different names, changed a few circumstances (Colette was actually on tour during the flood), and used their voices. The advantage was the voices. It was bliss writing dialogue between Colette and Gertrude Stein; I could have gone on forever. Q: The number twenty-eight appears quite often— George wants to throw twenty-eight copies of the Mona Lisa into the Seine; Milly’s birthday is January twenty-eighth. Does the number twenty-eight have an underlying meaning? SS: What an interesting question! There are twenty-eight bridges over the Seine, so George wants to throw twenty-eight copies into the river—one per bridge. January twenty-eighth, Milly’s birthday, was the date of the highest watermark during the flood. January twenty-eighth was also Colette’s birthday! But it’s all coincidence. Or the great artistic consciousness of the world secretly scheming behind our backs. Q: What do you want readers to get out of the book? SS: What does any writer want? I want to make the reader stay up all night with a story and never forget it; I want them to scream out loud with surprise, and cry, and laugh. Years from now I want them to look at somebody and say, “Oh, that person’s like Leonard; I understand him,” or “This is what happened to Madame Mallais or to Perdita; how she decided helps me.” I want readers to have a banquet, a feast. I want them to take away doggie bags full of goodies. I want more for them too: I want them to understand somebody better, consider something from another point of view, have a new image or a thought or a sense of possibilities. I want their lives to be not quite the same. I want it all. Doesn’t everyone? |

DVD Extras

New edition February 15, 2020.

430 pages. Trade paper, $15.99 ePub and MOBI $2.99 Preorder trade paper through Ingram-9781951636012 Universal book link for your favorite ePub site https://books2read.com/u/mVrPLp Kindle https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07ZDJSWYX |