Where stories come from: Witchcraft, magic, and film

Q: A Citizen of the Country reminds me of a fairy tale. There’s all the fortune-telling, the magic, stage magic, curses, haunted castles, transformations. Were you influenced in how you told the story by magic or fairy tales? Did you talk to any magicians?

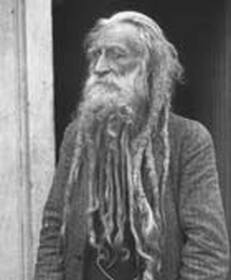

SS: Absolutely, by magic, fortune-telling, and fairy tales. In the book, the characters are making a film, a magic film, full of special effects. André, the director, is a stage magician; he runs the Grand Necropolitan horror theater and his specialty is showing people eaten by wolves onstage, people torn apart by madmen, that sort of thing. I looked at videos of a lot of magicians to see what André could do and how he’d think, and I have the great good luck to live near Beverly, Mass., where Marco the Magi and Le Grand David ran a volunteer company of stage magicians. I had a chance to talk to Marco the Magi—Cesareo Pelaez, who was one of the greatest modern stage magicians. And I read a wonderful book, which every mystery writer should run out and read, Henning Nelms’ Magic and Showmanship. Nelms was a magician and also a mystery writer (under the name Hake Talbot). He says the essence of magic is the essence of mystery-writing, which is to tell two stories at once. One story is what’s really happening, the strings being pulled and the endless rehearsal and the assistants running around behind the scenes. But the bigger story is the myth, the effortless marvel that the magician is creating for the audience. If you want to be a successful magician, that story must appeal to the deepest wishes and desires of the audience, to the audience’s love of the marvels beyond ordinary reality. Magic is witchcraft is making a myth. I was hugely influenced by fairy tales while I was writing A Citizen of the Country, and especially by a friend, Kelly Link. Kelly is amazing; she’s won the World Fantasy Award and the Tiptree Award for her reworkings of fairy tales, and I just kept saying, “Ooh, if only I could make this story feel like what she does.” (Read more about Kelly Link and the Interstitial Arts Movement, the home of American inter-genre magic realism) Q: How were you influenced by fortunetelling? SS: Fortune-telling is a sort of mythmaking, don’t you think? The fortune-teller gets out her cards and the audience is invited to ask a question, the most important question they can think of. The fortune-teller spreads out the cards, and there are all the big deep things of life in colored pictures: death, love, friends, betrayal, children. When you have your fortune told, you are opening yourself to the ultimate questions. I didn’t really talk to fortune-tellers because I’m scared of them. I have a friend who uses Tarot to plot her books, so I did a little experiment and used fortune-telling myself in writing Sabine’s parts of the book. Sabine uses a card deck called the Oracle of Napoleon. I got a copy from U.S. Games Systems, and every time Sabine told a fortune, I’d spread out the cards and use the way they came out. Q: Did it work? SS: Spookily! There’s one moment in the book when Sabine is trying to tell her own fortune, and all the cards except her own come out upside down. That actually happened, and I realized the cards were lying to her. I was so impressed I had to put it in the book. Q: In the past you’ve used real history—but this book is about witchcraft. SS: The book is about people who practice witchcraft, and in that sense it’s a real historical novel. What they practice isn’t modern Wicca or neopaganism. It’s a really, really old religion dating at least in part from before the Romans came to Gaul. The boves, the tunnels underneath the city where the “witches” meet, are real, two thousand years old. You can still take a tour of them. They really are unmapped and extend miles into the countryside. The castle where most of the book is set is a real castle—Mont St. Eloi, an incredible place, like Mont St. Michel or Stonehenge. It’s been a Christian holy place since 660 but it was holy to the local religion before then. You can see the ley lines converging on it. My witch, Sabine, grows up with these beliefs. She then goes to school in Paris, so she believes in demons because the Parisian occultists were big on that sort of thing. That part of her belief isn’t nearly as real. The beings she tries to summon were essentially made up by Arthur Edward Waite, who later did the Waite Tarot. But she believes in them—so she actually does call up a demon, though not the one she wanted; a modern demon, who thinks he’s a man.  A Flanders witch around 1910. A Flanders witch around 1910.

Q: Did you talk to any real witches or sorcerers while you were writing this book?

SS: I talked to some people who practice Wicca. But I couldn’t talk to any of the Flanders witches. As far as I knew, they were all dead. The picture here is what one of them looked like. Q: What happened to them? SS: The First World War. A Citizen of the Country is set in French Flanders, one of the most terrible battlefields of the First World War. In Flanders field the poppies blow Between the crosses, row on row… Before the war Flanders was a bit like Holland, a land of woods and streams and little villages, and it was full of sorcerers and magic. The sorcerers were solitaries—shepherds or, fairly often, priests. They lived in the little towns along the Arras road, or in the fields with the sheep. When the Germans invaded France in 1914, the German army dug in at Vimy Ridge—which you can see from the castle where my story is set. The Germans, the French, the British and Canadians fought here for nearly four years, and when they were done, the woods were nothing but splintered stumps in mud; the sheep had run away or been eaten; the villages had been bombed to the ground. Now, nearly a hundred years later, there are no woods and no villages; there are only flat beet fields, still pockmarked from the shelling. Fields near Vimy Ridge still can’t be plowed because so many unexploded shells are under the soil. And there are no more witches in Flanders. (Someday, I hope, I shall get a nice note from a witch in Flanders telling me I’m mistaken. (Later: I did. Witches now have email.) Q: Is Sabine really a witch? Why did you decide to write about someone so strange? SS: I think she’s being an ordinary person in an extraordinary way. She wants to practice sorcellerie—changing le sort, Fate. Don’t we all want to change our fate? In this book, everyone’s trying to change fate, either the fates of their families or what is going to happen when the war comes. André, Maurice Cyron, Perdita, the spies, Gilbert Knight… Reisden in particular tries to change André from a madman to a sane person, tries to change the doom of a family that’s been unhappy for generations, and he tries to change the fate of his own family for the sake of his son. Q: That’s not what I mean, though. Not everyone has supernatural experiences, but Sabine does; she sees when people are about to die. SS: She thinks she does. She sees a grey veil drop over people who are about to die. I actually know someone who used to see people who were dying. It was during the Second World War; she would see friends walking down the street and when the person came closer it was someone quite different. She’d think “How could I have taken this person for X?” And a day or so later she’d hear X had died. Q: Wow. SS: Yeah. It gave me the idea for what Sabine sees, the premonition, the precognition of someone’s death. But the person I know was scared, and Sabine’s delighted; she’s not going to die and it makes her feel great. Sabine isn’t an entirely good person—though I like her very much, and she doesn’t deserve what happens to her. Q: What would that be? SS: Now that would be telling. Q: You use silent filmmaking in A Citizen of the Country. Have you ever made films yourself? SS: Student films. Back when I was a film student in England (back when we used dinosaur-fat torches for fill lighting), there was no such thing as synchronized sound unless you had money, which we didn’t. So I wrote a lot of silent scripts, which came in helpfully here. I've acted a little, but I don’t really have a camera face. Instead I used experiences from other people, including Marty Meyers (thank you, Marty!) and Andreas Teuber, who as a young amateur actor acted with Richard Burton. While I was writing this I saw a lot of silent films on video. I have huge respect and love for them. Silent films are brilliant, they’re not just Keystone Cops shorts and jumpy, grainy prints. Film got sophisticated very early, especially trick films. The trick shot André is trying to get, a decapitation, is very old, about 4500 years. Ferdinand Zecca did something similar in 1901 at the end of this film. But Zecca used a jump cut; André's going to do it in one single shot. Q: Who designed the special magic effects in the book? SS:I knew what I wanted, and a couple of magician friends helped me work them out. Thank goodness for friends who know things! The tricks are supposed to work, but I wouldn't want to try the guillotine. Q: Filmmaking is a form of magic too... SS: Film is myth; film is a fairy tale. In films people really can live happily ever after. Sabine is not just a witch; she wants to be a film star. She sees herself on film and, in a real sense, she’s enchanted. She wants that fate, she wants to be that beautiful blonde on the screen, perfect for one moment that lasts forever. And she is. If this book ever gets made as a film, I want them to make parts of the silent film André makes, because I want to see Sabine on screen. She’ll be gorgeous. Q: Why did you call the book A Citizen of the Country? SS: It could have been called Theater of War, couldn't it? It’s a book about the countryside and country people—nobody’s more country than Sabine—but also about where you live and how you live there, how you take responsibility for creating a part of your world. You can make a myth; you can try to change fate; you can be a citizen and take responsibility; you can be a patriot; you can get married and have children. Laurie King said a lovely thing about this book, bless her, which is that there aren’t any bad people in it, or any wholly good ones; everyone is trying to do good in their own way. It reminds me of my favorite line in Rules of the Game: “The trouble is, everyone has their reasons.” That is as good a recipe as any for war and mayhem and destruction. Everyone in this book tries to do good in their own way, and it causes terrible troubles. They all have their reasons for doing what they do. And, like citizens in wartime, they end up caught up in events. A country is like family or fate; you think you own land, you try to own it; you try to own your family and your fate; but land and family and fate own you. You are the person you are because of how you take up your responsibilities toward your family, your piece of ground, the place where you live. Q: At the end of the book something major happens. Does this mean the trilogy is over? Will we ever see these people again? SS: I thought it would be a trilogy, but Perdita, who was busy looking after a small child in this book, said she'd like to do something more active, please. Could she go to America for a tour? And, so as not to worry Gilbert and Reisden, shouldn't she take a very safe boat--like Titanic? |

DVD Extras

New Director’s Cut Edition--available for preorder; published March 15, 2020

470 pages. Trade paper, $16.99 ePub and MOBI $2.99 Preorder through Ingram--9781951636029 Universal book link for your favorite other eBook site books2read.com/u/bxvkkq Kindle https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07Z9Y5WQC |